Aug. 27, 2019

Vitamin D: How much is too much of a good thing?

As health professionals and tennis enthusiasts who love to work out at the gym, Heather and Michael Giuffre (photo above) have always been interested in making diet and lifestyle choices that will keep them strong and healthy. When they heard the University of Calgary was looking for volunteers for a study looking at the effects of different doses of vitamin D supplements on bone health, they signed up right away.

“My mom has osteoporosis, and so do a number of our extended family members,” says Heather. “We’ve seen first-hand the effects of poor bone health and we want to do what we can to avoid it. There is so much conflicting information out there about how much vitamin D you should take. We felt this study was important.”

The Giuffres were participants in a study at the Cumming School of Medicine’s McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health. The study, released this week in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), showed there is no benefit in taking high doses of vitamin D. More research is required to determine if high doses may actually compromise bone health.

The vitamin D controversy

When bare skin is exposed to sunlight, it makes vitamin D, which is needed by our bodies to absorb calcium and ensure strong, healthy bones. With bathing suit skin exposure, it only takes about 10 to 15 minutes of sun exposure during the summer to generate all the vitamin D your body needs for the day. Unfortunately for Canadians, exposure to sunlight is diminished during the long winter months. This results in many turning to supplements to get the required vitamin D.

For normal, healthy adults, Health Canada recommends a total daily intake of 600 international units (IU) up to age 70, and 800 IU after age 70. Other sources, like Osteoporosis Canada, suggest adults at risk of osteoporosis, a condition characterized by bone loss, should take 400 to 2,000 IU of vitamin D. However, some people may be taking up to 20 times the recommended daily dose to prevent or treat a variety of medical conditions that might be related to having not enough vitamin D. So, what is the correct dose? And, how much is too much?

“Although vitamin D may be involved in regulating many of the body’s systems, it is the skeleton that is most clearly affected by vitamin D deficiency,” says Dr. David Hanley, MD, an endocrinologist in the Cumming School of Medicine (CSM), and one of the principal investigators of the study. “Current Health Canada recommendations were set to prevent the bone diseases caused by vitamin D deficiency for the vast majority of healthy Canadians. But it has been more difficult to clearly establish the optimal dose of vitamin D. When we designed this study, there remained a question whether there’s more benefit in taking a higher dose.”

Three years and 300 volunteers

The three-year study followed 300 volunteers between the ages of 55 and 70 in a double-blind, randomized clinical trial to test the hypothesis that with increasing doses of vitamin D, there would be a dose-related increase in bone density and bone strength. A third of the study participants received 400 IU of vitamin D per day, a third received 4,000 IU per day, and a third received 10,000 IU per day.

Vitamin D study participant Patricia Salo and researcher Steven Boyd with the XtremeCT scanner.

Don Molyneaux

Volunteers had both their bone density and bone strength measured using a new, high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan of bone at the wrist and ankle, called an XtremeCT, used only for research. The XtremeCT, located in the McCaig Institute’s new Centre for Mobility and Joint Health, is the first of its kind in the world, and allows researchers to look at bone microarchitecture in detail never seen before.

Standard dual-X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) bone density was also obtained. Participants received scans at the start of the study and at six, 12, 24 and 36 months. To assess vitamin D and calcium levels, researchers also collected fasting blood samples at the beginning of the study and at three, six, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months as well as urine collections annually.

There was a decrease in bone density with higher doses of vitamin D

Bone mineral density (BMD) is determined by measuring the amount of calcium and other minerals in a defined segment of bone. The lower the bone density, the greater the risk for bone fracture.

Adults slowly lose BMD as they age, and the DXA results showed a modest decrease in BMD over the duration of the study, with no differences detected between the three groups. However, the more sensitive measurement of BMD with high resolution XtremeCT showed significant differences in bone loss among the three dose levels.

Total BMD decreased over the three-year period by 1.4 per cent in the 400 IU group, 2.6 per cent in the 4,000 IU group and 3.6 per cent in the 10,000 IU group. The conclusion was that, contrary to what was predicted, vitamin D supplementation at doses higher than those recommended by Health Canada or Osteoporosis Canada were not associated with an increase in bone density or bone strength. Instead, the XtremeCT detected a dose-related decrease in bone density, with the largest decrease occurring in the 10,000 IU per day group.

“We weren’t surprised that using DXA we found no difference among the treatment arms, whereas with XtremeCT, the latest in bone imaging technology, we were able to find dose-dependent changes over the three years. However, we were surprised to find that instead of bone gain with higher doses, the group with the highest dose lost bone the fastest,” says Dr. Steve Boyd, PhD, a professor in the CSM and one of the principal investigators of the study. “That amount of bone loss with 10,000 IU daily is not enough to risk a fracture over a three-year period, but our findings suggest that for healthy adults, vitamin D doses at levels recommended by Osteoporosis Canada (400-2,000 IU daily) are adequate for bone health.”

Elevated levels of calcium in the urine with higher doses of vitamin D

A secondary outcome of the study explored a potential safety concern with taking high levels of vitamin D. Although there were incidences in all three arms of the study, the investigators found that participants assigned to receive higher doses of daily vitamin D supplementation (4,000 IU and 10,000 IU) over the three years were more likely to develop hypercalciuria (elevated levels of calcium in the urine), compared to those receiving a lower daily dose. Hypercalciuria is not uncommon in the general population, but is associated with increased risk of kidney stones and may contribute to impaired kidney function.

Calcium supplements may be a contributing factor. Hyperalciuria occurred in 87 participants. Incidence varied significantly between the 400 IU (17 per cent), 4,000 IU (22 per cent) and 10,000 IU (31 per cent) study groups. If hypercalciuria was detected in study participants, calcium intake was reduced. After repeat testing, the hypercalciuria usually resolved.

“What we saw in this study is that large doses of vitamin D did not improve bone density or strength,” says McCaig Institute member Dr. Emma Billington, MD, one of the authors of the study. “For most healthy adults, 400 IU daily is a reasonable dose for maintaining bone health, and no further bone benefit would be obtained with doses of 4,000 IU or higher.”

The research team

Dr. Steven Boyd, PhD, is a professor at the Cumming School of Medicine (CSM) in the Department of Radiology at the University of Calgary, and holds a joint position at the Schulich School of Engineering and the Faculty of Kinesiology. He is the Bob and Nola Rintoul Chair in Bone and Joint Research and the McCaig Chair in Bone and Joint Health. He is also the director of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health.

Dr. David Hanley, MD, FRCPC, is an endocrinologist and professor emeritus in the CSM’s departments of medicine, oncology and community health sciences. He is a member of the O’Brien Institute for Public Health, the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health and the founder of Alberta Health Services’ Osteoporosis Centre, now called the Dr. David Hanley Osteoporosis Centre.

Dr. Emma Billington, MD, FRCPC, is an endocrinologist and a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at the CSM. She is a member of the O’Brien Institute for Public Health, the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health and the associate medical director of the Dr. David Hanley Osteoporosis Centre in Calgary.

Dr. Lauren Burt, PhD, is a senior scientist in Steven Boyd’s Bone Imaging lab in the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health.

Dr. Sarah Rose, PhD, is a senior biostatistician with Alberta Health Services.

Funding was provided by Pure North S’Energy Foundation in response to an investigator-initiated research grant proposal. The funder did not have a role in conducting the study, analyzing the data or deciding to submit the article for publication.

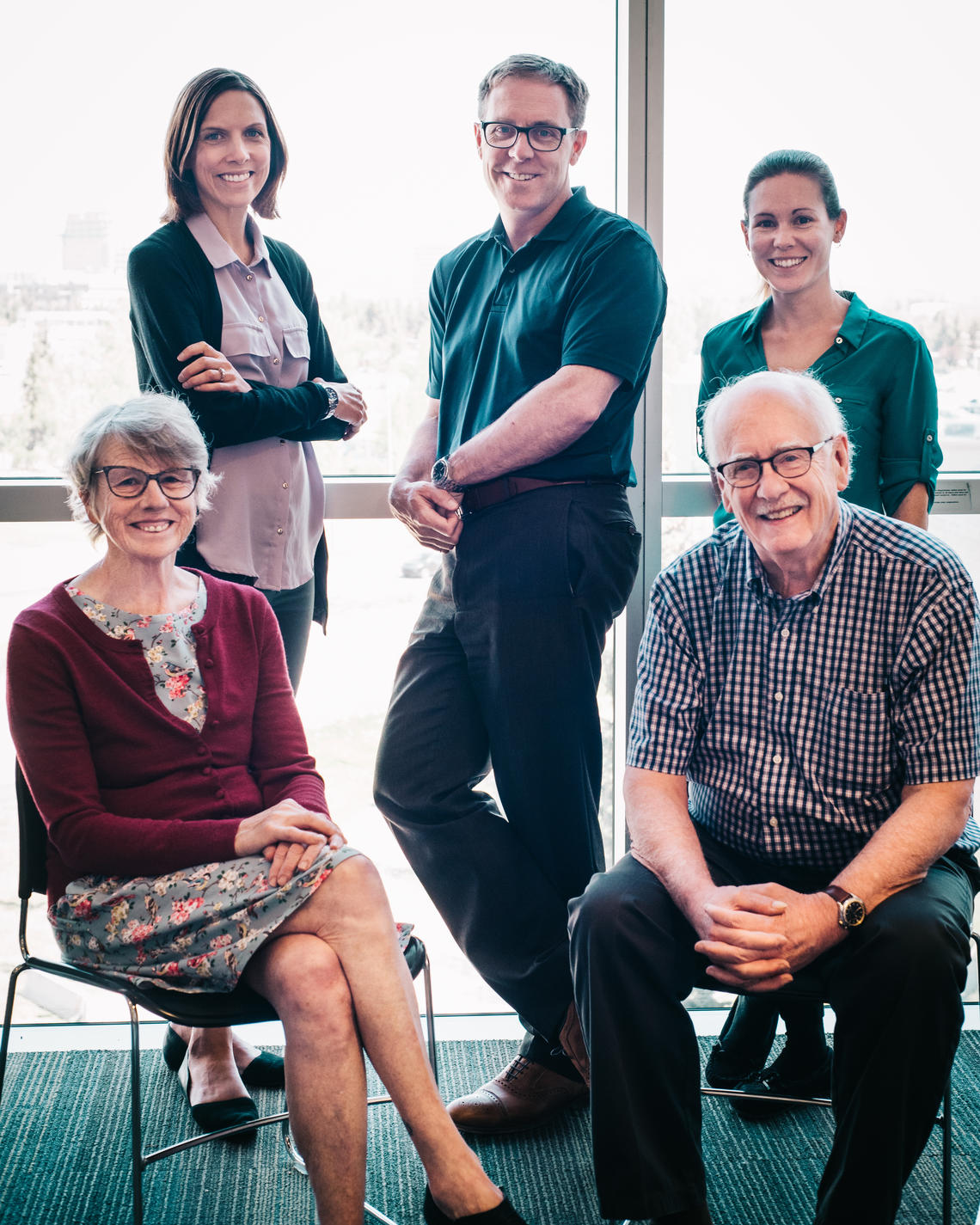

The vitamin D research team.

Nedaa Photography

Back, from left: Emma Billington, Steven Boyd, Lauren Burt. Front, from left: Sarah Rose, David Hanley.